What to do when your male friend is sexually assaulted

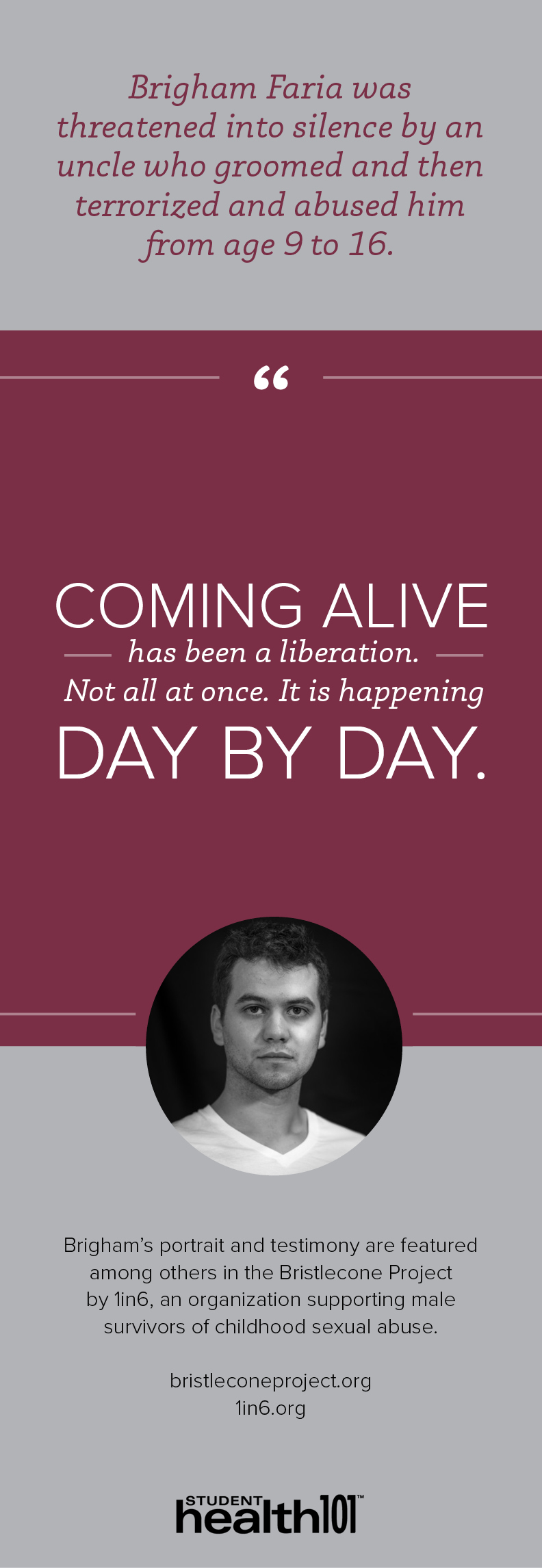

“I have been sexually assaulted. As a man, it’s not something you tell anyone, because everyone else just assumes you liked it or wanted it to happen,” wrote a second-year undergraduate at the University of Regina, Saskatchewan, in a recent Student Health 101 survey.

“As survivors, we need to hear that it’s not our fault and not be accused of lying when we share such a painful experience,” said a fifth-year student at the University of Alberta.

“Every time I have shared my story I got responses such as, ‘You wouldn’t have gotten [physically aroused] if you didn’t want it,’” said a second-year student at Lambton College, Ontario.

How social pressures and stereotypes harm men

Men who have had unwanted sexual experiences can experience many barriers to talking about those assaults. That’s why it’s so important that you, their friends and loved ones, know that you are well positioned to help—and how you can do that.

Many of the challenges men face reflect social pressure: ideas that sexual assault makes them less masculine, that women can’t assault men, or that “real men” don’t talk about (let alone get help for) painful experiences.

Stereotypes relating to another person’s identity should not determine how we try to support friends. “Sex, gender identity, and race can all influence how an experience like this affects someone, but it’s very important you have no presumption about what it feels like to your friend,” says Dr. Melanie Boyd, assistant dean of student affairs and lecturer in women, gender, and sexuality studies at Yale University, Connecticut.

“Some men fear that they will be seen as less of a man,” says Dr. Jim Hopper, a researcher, therapist, and instructor at Harvard Medical School. “If they’re heterosexual, they may fear people will doubt their sexuality. And if they’re gay or bisexual, they may blame the assault on their sexuality in a way that further stigmatizes their being gay or bisexual.”

Stereotypes relating to another person’s identity, whether it’s their sex, gender identity, or race, should not determine how we try to support friends, though these factors might affect their experience.

“It is important not to assume how a person experiences a sexual assault. It is a unique experience for each individual,” says Joan Tuchlinsky, Public Education Manager at the Sexual Assault Support Centre of Waterloo Region, Ontario.

Sexual assault of men is common

Twelve percent of sexual assault survivors are male, according to police-reported data from the Uniform Crime Reporting Survey (2010). The true prevalence is likely much higher. The General Social Survey from Statistic Canada suggests 88 percent of sexual assaults are not reported to the police (2009). In the same survey, 15 out of 1,000 Canadian men reported that they had been sexually assaulted (2009).

4 steps to helping a friend

Everyone is different. People’s varying personalities and circumstances affect how they respond to an unwanted sexual experience and what we can do to help. For example, some people want lots of hugs, some people don’t. The most important thing is to relate to your friend in a way that can help him feel empowered and connected. You’re in a great position to do this.

1. Be careful not to “other” him

As challenging an experience as a sexual assault may be, it’s not as though your friend is an entirely different person. The “othering” of people who have been assaulted—treating them differently—can be just as dangerous as shrugging off unwanted sexual experiences, according to researchers Nicola Gavey and Johanna Schmidt (Violence Against Women, 2011). Avoid thinking of the assault as something that cuts survivors off from the rest of the world: In fact, it’s up to you to be supportive and counteract that.

2. Truly listen and ask questions

Make sure to listen and focus on your friend’s feelings. “Listen to what the person is saying and then soak it in,” says Gabrielle Bouchard, Peer Support and Trans Advocacy Coordinator at the Centre for Gender Advocacy, Quebec. “Don’t try to find an answer.”

- Avoid pushing your own ideas. “Reassure them that it wasn’t their fault, no matter what the circumstances were. You want to be supportive and understanding and communicate your belief that healing is possible. Support the survivor’s decision in regards to their own healing, even if it’s to do nothing,” says Tuchlinsky.

- Don’t be an investigator. It’s not important for you to find out exactly what happened or to delve into the details beyond what your friend wants to share.

3. Be thoughtful about your language

Language is important. Specifically tell him you are not bringing stereotypes into this.

- Avoid pronouns that assume the perpetrator is a man—or a woman.

- Make clear that you are not making presumptions about your friend’s experience based on his identity, whether he is straight or gay, transgender or cisgender (of typical gender). Use cues such as gender-neutral pronouns or phrases like “people of all genders.” “You have no idea how fast people pick up on those cues. When you show openness, it does not go unnoticed,” says Bouchard.

- It is not your role to define the experience for your friend. Some people don’t use the word “rape” or “assault” to describe what may seem to you to be sexual violence, or relate to “victim” or “survivor.” “You want them to feel like you’re connecting with their experience, not trying to impose your views or language on them,” says Dr. Hopper.

4. Give him choices

“As a friend, you want to relate to them in a way that gives them power, including by giving them choices and respecting whatever choices they make on whatever timeline,” says Dr. Hopper.

- Whether your friend wants to pursue some kind of action may depend in part on your school’s disciplinary policy or other systems for dealing with sexual misconduct. It is up to him to decide. While it is not your job to steer him to the police or school administrators, providing information can be a great way to help. Figure out what resources your school has, such as hotlines, therapists, heath care providers, disciplinary processes, or survivor advocates. Informing yourself is essential.

- Talk with your friend about what makes him feel empowered and safe. Everyone’s different, so whether your friend feels like watching TV, working out, or flirting with someone at a party, you should ask and see how you can help. Some people want to nest, some people want to be social. It’s not your job to judge but to be supportive.

Don’t say that, say this

Avoid saying this

- There’s no way I can understand what you’re going through.

- How could you let that happen?

- If someone tried to do that to me, I’d fight them off.

- You’re never going to be the same.

- You’re endangering other people if you don’t tell the police.

- Now that you’re a rape survivor, you have to speak out about your experience.

- You must not have come to terms with it yet.

Maybe try this

- It means a lot that you trusted me with that.

- What can I do to help?

- Do you think you’d like to talk to a crisis centere or something like that?

- Don’t blame yourself.

- What would be an empowering/fun/etc. thing to do?

- I’m here for you.

Know any guitarists?

Check out the 1 Blue String campaign

|