Mind & body

A broader look at disordered eating

|

In how many ways can eating be disordered? Anorexia and bulimia are familiar terms, and you might have heard of binge eating disorder. What about orthorexia, rumination disorder, muscle dysphoria, drunkorexia, or night eating disorder? Some are clinical diagnostic terms; some have been coined in the community. These and other terms reflect the broadening recognition that disordered eating, eating disorders, and body image issues can manifest in many different ways—including out-of-control eating, obsessive weight-training, cutting out food groups, abusing certain medicines, skipping meals before drinking alcohol, and more. Often, these behaviours both reflect and reinforce emotional health challenges.

How self-criticism can harm us

In many cases (but not all), disordered eating is related to an urge to more closely resemble a popular physical type. “People often feel that peace with your body is conditional: ‘I’ll accept my body when I lose weight or when I exercise more often,’” says Dr. Megan Jones, clinical assistant professor at Stanford University and chief science officer at Lantern, an evidence-based program for improving body image and reducing disordered eating behaviours.

“However, research shows that when you are less self-critical and improve your body image, you’re actually more likely to do the things necessary to optimize your emotional and physical well-being.”

What do many people with eating disorders have in common?

Body image & shame

Negative body image

Thoughts and behaviours might include:

- Body-checking: Obsessively checking the mirror, scrutinizing parts of the body, or holding/pinching skin folds

- Self-scrutiny: Criticizing your own body, in your head or out loud

- Constant comparison: Comparing one’s own shape and size to that of others

Shame and guilt

Shame and guilt often follow the act of eating. People with eating disorders may feel unworthy of food as a source of nourishment, pleasure, or recovery.

- Shame is a feeling of being inherently flawed: “I am bad/wrong.”

- Guilt is feeling regretful about an action or behaviour: “I did something bad/wrong.”

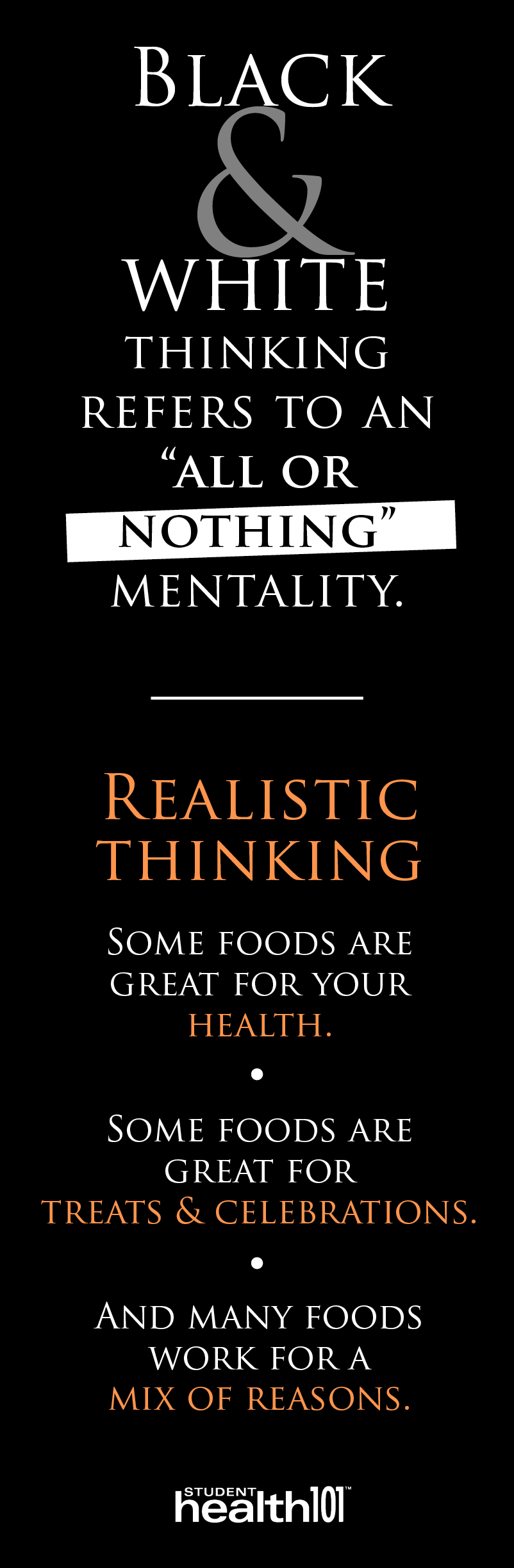

Black & white thoughts

Cognitive distortion: Black-&-white thinking

Cognitive distortions are destructive beliefs and self-judgments; these can reinforce eating disorder behaviours. Often, these are learned early in life.

Black-and-white (polarized thinking) is an “all or nothing” mentality that leaves no room for middle ground.

- Food choices are categorized as “good” or “bad”, “safe” or “unsafe”.

- Black-and-white thinkers tend to alternate between extreme behaviours specific to food and exercise (all or nothing).

- Typical thought: “I already blew it by eating that cookie with lunch… Now I’m just going to eat whatever I want for the rest of the day and start over again tomorrow…”

Cognitive distortions

Personalization, mind-reading, and blaming

Personalization

- Constantly measuring one’s worth by comparing oneself to others

- Typical thought: “I’m the biggest person in this room.”

Mind-reading

- Making assumptions about what others think of us without substantial evidence

- Typical thought: “I hate grocery shopping because when I have lots food in my shopping cart, everybody around me is thinking I’m a fat pig, and I can’t handle that.”

Blaming

- Taking the victim role: e.g., “They made me feel bad about my body so now I don’t care; I’m just going to binge on whatever I want.”

- Blaming ourselves: e.g., “My ex broke up with me because I’m not good-looking enough.”

Cognitive distortions

Over-generalization and catastrophic thinking

Over-generalization

- Taking a small piece of evidence or a one-time event and jumping to conclusions about “always” or “never”

- Typical thought: “I gained weight this weekend… I will keep gaining weight every weekend for the rest of my life.”

Catastrophic thinking

- Worrying about worst-case scenarios

on a regular basis - Typical thought: “What if I lose control around food? If I’m alone then it’s possible, and since I will be alone later then it will definitely happen to me…”

Rigidity & isolation

Extreme rigidity

- Calorie-counting and setting a daily calorie allowance

- Strictly measured portions

- Food rules: cutting out certain types of food

- Limited variety; lack of flexibility: eating the same foods or food combinations every day

Social isolation

- Avoiding social situations centered around food, such as restaurants, birthday celebrations, and holiday parties

- Stems from fear of being judged or feeling pressured to eat a food that makes them anxious

Student story

“People socially isolate themselves because they are consumed by their eating disorder. It affects everything—overall demeanor, attitude towards others, mood, self-confidence, and priorities.”

—Dakota B., first-year graduate student, University of Ottawa, Ontario

Official eating disorders & related diagnoses: old & new

In 2013, the American Psychiatric Association updated its categories of eating disorder in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). The new diagnostic criteria are intended to support more individualized treatment approaches and achieve better outcomes.

These descriptions are abbreviated; they do not include information on the frequency and duration of relevant behaviours. Eating disorders should be diagnosed by a health care professional with relevant expertise and qualifications.

- Anorexia Nervosa: Restriction of energy intake (calories) leading to a significantly low body weight, with intense fear of gaining weight and often denial of the seriousness of low body weight; “subthreshold” anorexia nervosa involves similar behaviours with a normal body weight

- Avoidant/Restrictive Food Intake Disorder: Restrictive eating patterns ranging from feeding problems in infancy to restrictive eating in a young adult afraid of choking or vomiting; the causes are psychological but do not involve distorted body image or weight concerns

- Binge Eating Disorder: Binge eating not followed by compensatory behaviours; “subthreshold” binge eating

disorder involves similar behaviours with less frequency - Body Dysmorphic Disorder: Extreme preoccupation with a perceived flaw in appearance, interfering with daily life; not an eating disorder per se, but may accompany one

- Bulimia Nervosa: Binge eating (eating abnormally large amounts of food, past the point of feeling full, and feeling out of control while eating) followed by compensatory behaviours, e.g., self-induced vomiting, abuse of laxatives and diuretics, or excessive exercise; “subthreshold” bulimia nervosa involves similar behaviours with less frequency

- Muscle Dysmorphia: Extreme preoccupation with the desire to have a muscular physique; not an eating disorder per se, but may accompany one

- Night Eating Syndrome: A pattern of eating very late in the evening or in the middle of the night

- Pica: Repeatedly eating non-food substances, e.g., dirt, clay, chalk, or laundry detergent; most often seen in pregnant women or people with iron-deficiency anemia

- Purging Disorder: Compensatory purging behaviours without binge eating

- Rumination Disorder: Regurgitating food, then re-chewing, re-swallowing or spitting it out; may be present with anorexia or bulimia

Eating disorders VS Disordered eating

Eating disorders:

- Eating disorder refers to a serious psychiatric illness involving intrusive thoughts and actions related to food and weight that interfere with physical, social, and emotional health. They can affect anyone at any time. “We’re still combating the idea of who struggles with eating disorders. The truth is that people of all genders, all ages, and [all] cultures, can struggle with eating disorders,” says Lindsey MacIsaac, the Program Coordinator at Hopewell Eating Disorder Support Centre in Ottawa, Ontario.

Eating disorders vary; they tend to involve behaviours like these:

- Restricting food intake

- Binge-eating: consuming large amounts of food in a relatively short time frame, to the point of feeling out of control and uncomfortably full

- Purging: self-induced vomiting, abuse of laxatives, or diuretics

- Use and abuse of diet pills

- Compulsive exercise with the goal of burning calories: More info

Engaging in multiple methods of compensatory behaviours (efforts to purge or offset calories from food) is associated with more severely disordered eating.

Disordered eating:

- Disordered eating is a broader term that describes an unhealthy relationship with food. All eating disorders involve disordered eating. But someone with disordered eating does not necessarily have a full-blown eating disorder.

Signs of disordered eating include:

- Abnormal, quirky behaviours and patterns related to food and eating

- Changes in eating patterns due to temporary stressors, high-pressure events, or an injury or illness

- Obsession and extreme rigidity around food choices

- Anxiety related to eating certain foods or eating in certain situations, e.g., with a large group of people

- Attempts to offset the calories from alcohol consumption (e.g., avoiding food or exercising obsessively)

What are “orthorexia,” “drunkorexia,” and other unofficial eating disorders?

Orthorexia

Restricting the type (but not the amount) of food to the point that it negatively affects quality of life: “healthy eating” taken to an extreme. Research suggests “orthorexia” may be related to obsessive-compulsive disorder and may be more prevalent in men than women.

Student story

“I cut out basically everything that wasn’t a fruit or vegetable—no grains, meat, dairy, nuts, or legumes. When food is viewed as an enemy, you’re constantly fighting with yourself, seeing cravings or just even the feeling of hunger, as a detriment or weakness.”

—Kaitlyn A., fourth-year undergraduate, Western University, Ontario

Drunkorexia

Restricting food or exercising obsessively to compensate for calories from alcohol. Research shows a strong association between heavy drinking, high levels of physical activity, and disordered eating in college students, according to a 2012 study in the Journal of American College Health. “Drunkorexia” is more prevalent among women than men and is motivated by concerns about body weight, according to a 2014 study in the same journal.

Pregnorexia refers to a resistance to gaining weight during pregnancy.

Diabulimia refers to behaviours in people with insulin-dependent (Type 1) diabetes who restrict their insulin to manipulate their weight.

What contributes to disordered eating?

Disordered eating likely reflects a combination of risk factors. Researchers are exploring many of these influences:

- Genetics

- Certain personality traits; e.g., anxiety, perfectionism, competitiveness, hyperactivity, and compulsiveness

- Emotional health issues; e.g., traumatic experiences, addiction, depression, and stress

- Environmental influences:

- Idealized media images reinforce

a narrow definition of attractiveness - Dieting in early life is related to eating disorders and obesity later

- Social pressure and judgment (“body shaming”) contribute to eating disorders and obesity

- Life transitions can increase exposure to possible triggers

- Performance pressure—e.g., among athletes—can contribute to stress relating to body weight and shape

Helpline, treatment referrals, support groups, and tool kits

How common is this among students?

How to get along better with your body & your food

Here’s how Nicky Gitlin, RD and eating disorders specialist in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan, breaks it down:

- Mindful eating: using the five senses to fully experience foods

- Self-care: nourishing the body and mind with a range of nutrients

- Self-worth: feeling worthy of food, health, and happiness

- Intuitive eating: being in touch with our hunger and fullness cues

- Flexibility and variety: choosing different foods and meals from day to day, without stress or anxiety

Why body shaming fails and how you can counteract it

Body shaming (criticizing your own looks or someone else’s) can reinforce destructive self-beliefs and drive disordered eating behaviours, according to research“Body shaming is definitely an issue. I think it’s important to recognize beauty in everyone,” says Diana M., a second-year graduate student at Carleton University in Ottawa, Ontario.

Focus less on weight and body shape in your conversations. You may think you’re complimenting someone by saying, “Have you lost weight?” or “You look like you’ve been working out.” But you’re actually reinforcing the stereotype that thin means beautiful or that muscular means good looking.

Discuss the health and emotional benefits of healthy eating and physical activity, rather than their impact on appearance. For example, ask your friend whether the dance classes are helping him feel stronger or sleep better.

- Resist criticizing your own body. If your friend or family member criticizes theirs, say, “You know I love you, and it hurts me to hear you say that about yourself.”

- Worried about your friend’s disordered eating? Here’s how to talk to them about it.

How and why to tune out some of that media stuff

In a recent Student Health 101 survey, nearly 70 percent of respondents said the media’s portrayal of unrealistic body images affects the way they feel about their own body. Research has shown benefits from interventions that help people become more aware of the influence of the media on their body image, according to an analysis published in BMC Psychiatry (2013).

- Photoshop® and lighting are extensively used to make actors and models appear thin, chiseled, and flawless. Sometimes, they take things too far. For examples, search online for “Photoshop mistakes.”

- Many actors dedicate considerable time and energy to diet and exercise, especially if their roles require a certain body type. That’s their job. It’s probably not yours.

- The media play to our insecurities in order to sell us something—like miracle creams and get-buff-quick products (which don’t work).

“Beauty standards come from popular culture and mainstream media. It’s optimal muscle mass for men and the hourglass shape for women. They literally make it unattainable.”

—Nick Y., fourth-year undergraduate, University of Manitoba

“The media has created this idea that certain body types are ‘bad’ body types. Comparison will lead to a lot of unhealthy behaviours and expectations for all individuals.”

—Stephanie F., fifth-year undergraduate, University of Alberta

Hang out with people who nourish your self-belief

- If a friend or family member comments on your weight (positive or negative): “Thank you, I care about my health, but I try not to let my weight be a focus.”

- When you’re tempted to compare your own looks to someone else’s, try to think about their—and your—positive traits that aren’t related to appearance. What do you admire about their personality? What might they admire about you?

Student story

“When you have a negative body image, it’s difficult to change that on your own. It’s very important to be around supportive people.”

—Lija S., second-year student, Athabasca University, Alberta

Student story

“I’m native and, as a women who does not fit into society’s image of beauty, I live a life with a split mind. One part of my mind knows I’m beautiful, while the other is heavily influenced by the way the world views women. I used to try to conform to the standards that were set by other people. I had a professor that made me understand my perspective on beauty and body image. My friends and I went through the class together, and it made our support for each other much stronger.”

—Shaunte J., fourth-year undergraduate, Blue Quills First Nations College, Alberta

How to disempower your inner critic

- “I like that I can dunk a basketball.”

- “I’m really good with kids and can’t wait to finish my degree in elementary education.”

- “I’m a pretty darned good computer programmer, if I do say so myself!”

- “I’m a supportive and loyal friend.”

“Silencing the inner critic is a key step in the process [of accepting your body]. But it also involves being willing to let go of that critic.”

—Dr. Megan Jones, chief science officer at Lantern, a program for improving body image and eating behaviours

“Make a list of things you like about yourself that aren’t related to what you look like. Everyone has strengths; what are yours?”

—Dr. Rebecca Puhl, deputy director of The Rudd Center for Food Policy and Obesity and professor at the University of Connecticut

“What our bodies can do has more value than what they look like. If someone says they like how their legs look, try saying, ‘Great! So glad you like that about yourself. Your legs also allow you to walk to your friend’s house to hang out with him or her.’”

—Lindsey MacIsaac

Get active to help your body and mind support each other

Almost any type of regular physical activity can help people feel better about their bodies, regardless of the effects on their fitness and body shape, according to a 2009 meta-analysis of studies by researchers at the University of Florida.

Student story

“As someone who has struggled with disordered eating and body image since my early teens, I understand the temptation to punish my body. It is very easy to hate yourself in a world that trains you to critique and loathe your body for what it isn’t instead of appreciate it for what it is. Physical exercise forces you to come to terms with the fact that your body is a miracle, and can lead to positive body image and an increased sense of accomplishment and self-worth.”

—Second-year undergraduate, Mount Allison University, New Brunswick

When exercise isn’t working

If you find yourself exercising compulsively or punitively to compensate for what you’ve eaten or drunk, this may be a symptom of disordered eating.

Try a self-guided online intervention

Some internet-based interventions appear successful in preventing and/or treating eating disorders, according to studies. For example, The Looking Glass Foundation, an eating disorder support centre based out of Vancouver, British Columbia, offers online support groups and chat lines. There may be other options available through your counselling centre or the eating disorder support centre in your province or territory.

Helpline, treatment referrals, support groups, and tool kits