Students’ stories

Surviving sexual assault and other trauma

|

The process of surviving sexual assault, sexual abuse, and other traumatic experiences is unique to each individual and can be difficult to predict. “Every survivor’s experience of sexual assault is different, and that means that every healing process is just as unique,” says Frances Maychak, External Coordinator at the Sexual Assault Centre of the McGill Students’ Society in Montreal, Quebec.

If you’re a survivor of trauma, those around you may have expectations about how you should react and how long your recovery should take. It’s important to develop strategies that fit with your own priorities, circumstances, and needs. “Survivors deserve to be supported and to have their agency respected,” says Maychak. Here, students—women, men, gay, straight—describe what helps them in the aftermath of sexual assault and abuse.

Student survivors share what helps

“I found a support group”

“I was sexually assaulted by a family member as a child. I spent 10 years suppressing the memory and acting like it never happened. I grew up wondering why my thoughts and behaviours were not ‘normal’ and feeling like everything was my fault. It was only when I met my current boyfriend that I finally opened up about my experience and acknowledged it. That was when I decided to come to terms with it and to try and heal. My first step was realizing that even though I did not have the choice back then, I did have a choice about whether or not I wanted to recover.

“I decided to start online and research numerous support groups for survivors of sexual assault. I was surprised to see so many others out there; I had always thought that I was alone. The comfort and understanding I got from these support groups really helped me and showed me that I could and would get through this. I wish I hadn’t waited so long to do that for myself. It is never too late to do what you need to do to feel better. Take all the time you need and when you’re ready, you can get through this.”

—Undergraduate, Regional School of Nursing, Grenfell Campus, Memorial University of Newfoundland

“I talk with a counsellor”

“A day or two after I was attacked, I wasn’t doing well. My roommate, who is a social work major, pushed me to go to the campus counselling service, to make sure I was making decisions that were best for me. They talked me through what happened and my next steps. The same psychologist was by my side the whole time, making sure I was OK. They had me get a physical and do STI tests, but their main goal was to get me talking and for me to regain my body-to-mind connection, which tends to get distorted when you get traumatized.

“The most comforting thing about them was that they don’t pressure you to talk or do anything that doesn’t feel comfortable. The most important advice they gave me was to realize what happened and to work on getting better. Cliché, I know. But when something like sexual assault happens, you can’t just block it out. By ignoring it, you prolong the healing process. I still check in with them once a week to tell them how I’m progressing and the successes and struggles of the week.”

—Undergraduate, Temple University, Pennsylvania

“I got justice through the legal system”

“The other guys on the team labeled me gay, homo, fag… Each guy held me down and took his turn forcing me to do things I did not want to do. What’s important is seeking closure within yourself. The only reason I can wake from the nightmare is because I took it upon myself to [file charges against] every single one of them. I made sure that they either spent time in jail or were charged a huge chunk of money. Although someone might not understand what you’re going through, you need to tell someone. You need to report what happened, who, when, where, everything, to the best of your abilities.”

—Second-year undergraduate, University of New Brunswick, Fredericton

“I work on self-care and creativity”

“I’m not someone who feels comfortable talking about my emotions, and I found that keeping busy [after the assault] really helped. I joined a couple of community classes that were all completely different. I tried kickboxing, which helped me get, and eventually feel, stronger. I also took some art classes and a makeup artistry course. Though I didn’t join these programs as a way of recovering, I now see how they all gave me a way to express my feelings and move on.”

—Third-year undergraduate, York University, Ontario

“I contacted a rape and sexual assault crisis centre”

Student’s story

“I had an advocate available via phone any time I had to talk. She was the most understanding and caring lady in the world, and even came with me to court so I didn’t have to be alone. Women and men should know that they can speak up about sexual assault immediately and get in touch with sexual assault advocates. They might need help getting out of the situation and dealing with what already transpired. It needs to be talked about. Keeping it inside will eat you alive.”

—First-year undergraduate, Ridgewater College, Minnesota

What this is and how it works

Most provinces and territories, and some universities, have rape and sexual assault crisis centres that offer a wide range of services that may include counselling, STI testing, and legal advocacy and guidance. According to a 2006 study in Violence Against Women, survivors who worked with a victim advocate were more likely to have police reports taken and less likely to say they felt further victimized by the police. They received more medical services and reported less stress as a result of the legal and medical processes.

“I was supported by my university”

Student’s story

“The first step [in recovery] was just realizing what had actually happened to me. It was like being hit by a truck, and I didn’t have time immediately after the [assault] to see who or what it was that harmed me. I just kept trying to erase the memory from my body, and I developed anorexia, bulimia, and PTSD as a result. I [eventually] brought my diagnoses to Disability Services at my university. They made study accommodations and formalized them in a professional manner, which prevented me from having to rehash (and relive) my story with each of my professors.

“I think the best thing that anyone who has experienced sexual assault as a student can do is get support from a doctor and work with services at their university. Since my diagnoses have been formally acknowledged by my university, I am on a modified schedule. Mental health crises are just as real and debilitating as physical disabilities, and the university will help to accommodate for them. My abuser stole from my body, but I refuse to let him steal from my future.”

—Former undergraduate, Trent University, Ontario

How schools can help

Survivors can be helped by a timely and adequate response from their school administration. “Schools can help with survivors’ healing by taking steps to understand what the recovery process looks like [for them] and working to accommodate survivors on that journey as best they can,” says Samantha Pearson, Education Program Coordinator at the University of Alberta Sexual Assault Centre.

“Things like granting exam or paper deferrals when a survivor is in crisis and can’t focus, switching a survivor out of a class if they feel unsafe, or even just knowing what resources are available on campus can make a huge difference in a survivor’s life.”

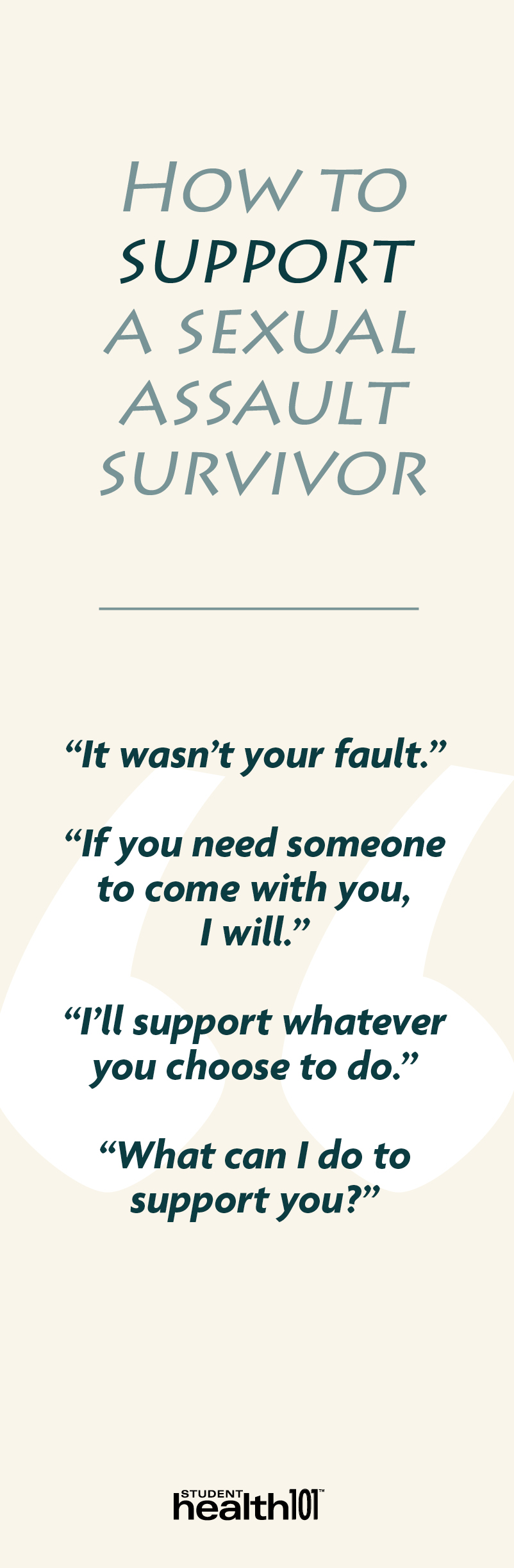

“I confided in supportive friends”

Student’s story

“I’ve heard stories of people blaming the victim, and that made me hesitant to open up to my loved ones. When I finally built enough courage to talk to my best friend, it felt like such a huge relief. She was supportive, understanding, and non-judgmental, all qualities that were very important. She didn’t push anything on me and was a really good listener, which was what I needed at the time. Telling someone else about my experience made it much more real, but it also made it easier to deal with.”

—Undergraduate, The University of British Columbia

How it helps

It’s important to spend time with friends and others who validate your feelings, don’t judge you, and make you aware of your strengths. Supportive reactions from family, friends, and counsellors help survivors recover, according to a 2006 study of 500-plus female college students in the Journal of Traumatic Stress. Negative reactions from friends and family are related to higher levels of post-traumatic stress.

“I drew on religious and spiritual support”

Student’s story

“I was raised a Christian, and I had a great pastor. The things he taught me about forgiveness and the power of prayer were a tremendous blessing, something I was able to fall back on when I experienced the trauma of rape. I realized if you don’t forgive, it’s like that knife of pain they put into you. You’re just digging it around in your belly, saying, ‘This is what happened to me; look how they hurt me! Look how sharp this knife is!’ Forgiveness is the act of pulling that knife out and dropping it. It hurts, but it’s not because they deserve to be forgiven. It’s because you deserve to walk free of it. Go to God in prayer. By praying for good things for that person, you create new emotions within your own heart that will heal the pain they left you in. It doesn’t make it right, what they did to you. Nothing makes it right. But forgiveness is the only way to take that knife out.”

—Third-year undergraduate, Pacific Lutheran University, Washington

How religion can help

Among survivors, positive religious coping—drawing on religion as a source of strength, meaning, and healing, rather than blame or punishment—is linked to greater emotional well-being, including lower levels of depression, according to a 2010 study in the Journal of Interpersonal Violence.

“I got involved in sexual assault prevention advocacy”

Former student’s story

“Speaking about one’s own experience, whether privately to friends, family, and counsellors, or publicly to groups at Take Back the Night marches, when the survivor feels ready, can be very therapeutic. Going public about my assault has made a huge difference. It’s been cathartic, turning a negative thing into action. You weren’t able to stop what happened to you, but you can help others. I’ve been down this road and can help explain it.”

—Dr. Laura Gray-Rosendale, author of College Girl: A Memoir (Excelsior Editions/SUNY, 2013), survivor of sexual assault, and professor of English at Northern Arizona University

Student advocacy organizations: Who they are and what they do

Many organizations that work to end sexual violence are staffed by sexual assault survivors. Student-oriented organizations such as Know Your IX, End Rape on Campus, and It’s On Us work to empower survivors and educate the public on the nature and impact of sexual assault.

They offer survivors:

- Support and understanding

- The opportunity to help others

- Education on, and insight into, sexual assault

- The opportunity to develop advocacy and related skills (e.g., in leadership, communication, and community or media outreach)

Male survivors

- Twelve percent of police-reported sexual assaults were filed by male survivors, according to police-reported data from 2010 (Statistics Canada). However, it is estimated that 88 percent of sexual assaults against both males and females are not reported, according to data anaylsis from the 2009 General Social Survey.

- In the US, 1 in 33 men experience an attempted or completed rape in their lifetime, and 1 in 6 have been raped or sexually abused by age 18, according to the Department of Justice (2000).

- Male survivors are likely to encounter the societal myths that men should be able to protect themselves and that male sexual arousal indicates willingness. These misconceptions can increase feelings of isolation and shame and may cause some to question their sexuality. This can contribute to self-destructive behaviours, such as substance abuse and social withdrawal.

LGBTQ survivors

- Lesbian women, gay men, and bisexual people are more likely to experience sexual assault, robbery, and physical assault, according to the 2004 General Social Survey. Self-reported instances of violent victimization among bisexual people were four times higher than the rate for heterosexuals, while the rate for gay men and lesbian women was more than double.

- Fifteen percent of those who identify as gay or lesbian and 28 percent of bisexual individuals experienced spousal abuse.

- 1 in 5 transgender people reported experiencing physical or sexual assault, according to an Ontario study (2010).

- In the US, almost two out of three transgender respondents say they have been sexually assaulted, according to the National Transgender Discrimination Survey (2011).

- Gay and transgender survivors may feel that the assault occurred because of their sexual and/or gender identity (this is sometimes true). Concerns about being shamed, blamed, and discriminated against by police, medical workers, and/or the community are barriers to reporting sexual assault.

Signs that you may need additional support

For a variety of reasons, some survivors of sexual assault may turn to coping strategies that prove less helpful in the long run. “Sometimes, people can hurt themselves or engage in self-destructive behaviour in the aftermath of a sexual assault. They may experience depression and sadness that make daily life difficult and use substances like drugs and alcohol to self-medicate,” says Andrea Gunraj, Communications Specialist at METRAC, in Toronto, Ontario. “These are understandable reactions and can help someone make it through the moment, but they can pose risks for their future health. An approach that [helps] survivors reduce the negative outcomes in their healing choices while [encouraging] them to continue to seek healing benefits is helpful in these circumstances.”

Potentially unhealthy coping strategies can include:

- Avoidance and denial

- Social isolation

- Risky behaviours, e.g., substance misuse and unsafe sex

Avoidance and social withdrawal

Avoidance coping involves distancing yourself from trauma as a way to avoid feeling overwhelmed. After a sexual assault, some decide to stay silent for reasons related to fear and perceived safety, blame and shame, or a desire to move on quickly. Sometimes, denial can help survivors maintain other aspects of their lives. However, avoidance may bring increased stress later.

“Avoidance is a normal response to trauma. When the person is ready to talk and reach out, support people need to be available and present,” says Carol Bilson, the Anti Violence Project Coordinator at the University of Victoria, British Columbia.

“Pretending that it hasn’t happened or ignoring it can be one of the worst things a survivor can do,” says Dr. Gray-Rosendale, author of College Girl: A Memoir. “This could not only result in the perpetrator going free, but also time and attention is needed to process and heal from what has happened.”

Some survivors withdraw socially. This is understandable, but may deny them the support of friends, family, and others who can potentially help.

Student’s story

“I felt responsible, so I didn’t want to share. I thought everyone would judge me and I would be alone, so I kind of made myself alone for a bit.”

—(University withheld)

Risky sexual activity and substance use

Risky behaviours include:

- Earlier initiation of sexual activity

- A greater number of sexual partners

- Not using a condom

- Unwanted pregnancies

- Alcohol and substance abuse

Survivors may feel the need to use substances or other physical sensations, such as sexual activity, to distance themselves from the memory of the assault or regain a sense of empowerment and control, according to the Southern Arizona Center Against Sexual Assault.

Deciding whether or not to report

Seeking justice through the legal system does not erase an assault or its effects, yet for some survivors the process is important to their recovery. Reporting an attack may help protect others. Reporting an assault can have downsides. A victim advocate at a sexual assault crisis centre or helpline can talk you through the pros and cons. Before disclosing an assault to any professional, on- or off-campus, ask them about confidentiality.

Survivor’s story

Former student’s story

“My parents helped me talk to an attorney, and I filed a civil lawsuit. I have not received any financial settlement, but what mattered was that my voice was heard. I felt enormously empowered, like I had reclaimed my inner strength. I no longer felt like an empty shell with my insides scooped out. It helped me to stop seeing myself as a victim. It also helped me publicize a terrible wrong that had been committed against me. By visibly pointing at my perpetrator and the people who protected him, I forced them out of the shadows and into the glare of the legal system and public opinion. I don’t think I could have recovered without taking action. Had I listened to my fear, I would always see myself as someone who was trampled on and could not get back up because she was too broken.”

—Former undergraduate, University of California in Irvine

How counsellors can help

Counsellors are trained to listen without expressing judgment. Many have helped others through similar situations. Additionally, counsellors can help you to:

- Sort through your emotions in a supportive environment

- Make decisions about reporting, legal options, and recovery

- Develop healthy coping strategies

- Minimize self-blame, guilt, and depression

- Continue your post-secondary education

Self-care strategies

“The most helpful thing I can say to someone who has experienced something traumatic is to be gentle on themselves—they’re not alone in feeling the way they feel, and they’ve made it this far,” says Samantha Pearson, Education Program Coordinator at the University of Alberta Sexual Assault Centre.

Self-care and creativity can involve:

- Healthful eating

- A sleep schedule that’s as normal and regular

as possible - Avoiding stimulants and depressants, e.g., caffeine, sugar, alcohol, and other drugs

- Mindfulness meditation

- Avoiding stressors to the extent possible

- Relaxing activities, e.g., reading, journaling, breathing exercises, yoga, meditation, and music

- Creative activities, e.g., music, writing, dance, and art

- Physical activity, which can reduce stress and help you feel more in control of your body